In 1972, I rode my bicycle to the library and checked out the book Go Ask Alice. There was buzz about it at school. It was a diary written by an anonymous teenage girl. And despite her good family life with attentive parents, “new” friends slipped the girl LSD one night, which proved to be the gateway to a disastrous drug addiction. And worse.

I had read nothing like it, and tore through the pages. As a teen girl, I found her thoughts on school, friends, and parents relatable. But I did not know how close it would hit home. When I got to the diary entry where she started popping sleeping pills to counter the speed she was taking, it became terrifying. I knew all about sleeping pills in my home.

I had seen my mom doling out Dad’s sleeping pills to him. I suspected she was afraid that the combination of drinking too much and Seconal might be lethal, so she became his gatekeeper. The thing is, though, I knew where she hid them. I had found them over a year ago, stashed in the drawer of the linen closet. The book reminded me that I could experiment at any time if I chose to. Where could it lead? Did I have the strength to control myself? I wasn’t sure.

And then, the book’s blunt Epilogue fractured me.

“The subject of this book died three weeks later after her decision not to keep another diary. Her parents came home from a movie and found her dead. They called the police and the hospital, but there was nothing anyone could do.” – Go Ask Alice 1971

A real girl had overdosed. My wobbly sense of safety crashed, seeing that she had not survived her drug choices. I had previously taken solace because, at least, she had survived everything she had ingested. Now, the worst had happened. She couldn’t fight herself; she couldn’t control it.

Imagine what it felt like to learn years later that the diary was a hoax. There was no girl, no diary, and no overdose. Beatrice Sparks, a woman of Morman faith, claimed she “found” the diary when, in truth, she wrote it to scare teen girls and boys away from drugs. The problem with me was that I wasn’t taking any pills; it was the book itself which offered up the possibility that I could.

Apparently, I was also not the only one living with anxiety over the book.

I found Sloan Tanen sharing her experience on electricliterature.com.com:

“I became terrified of social gatherings. I swore to myself that I would never do drugs and that, if I happened to find myself at a party by mistake, I would never accept a drink from a stranger. I vowed that if I ever took drugs ‘by accident,’ I would check myself into a rehab facility immediately to avoid any possibility of addiction. Only a twelve-year-old neurotic could rationalize such thinking, but it felt very real at the time.”

Gemini summarized that “Go Ask Alice traumatized a generation of young readers by functioning as a ‘scare tactic’ that induced extreme anxiety, paranoia about drug use, and a fear of losing control.”

There it was, a fear of losing control. That was my greatest fear.

I feel like if I had known it was fiction, that would have been an important safety net. Where do writers fall regarding this practice of labeling a work of fiction as non-fiction? It can be a successful strategy for higher book sales. But is there any responsibility involved, especially with young adult material?

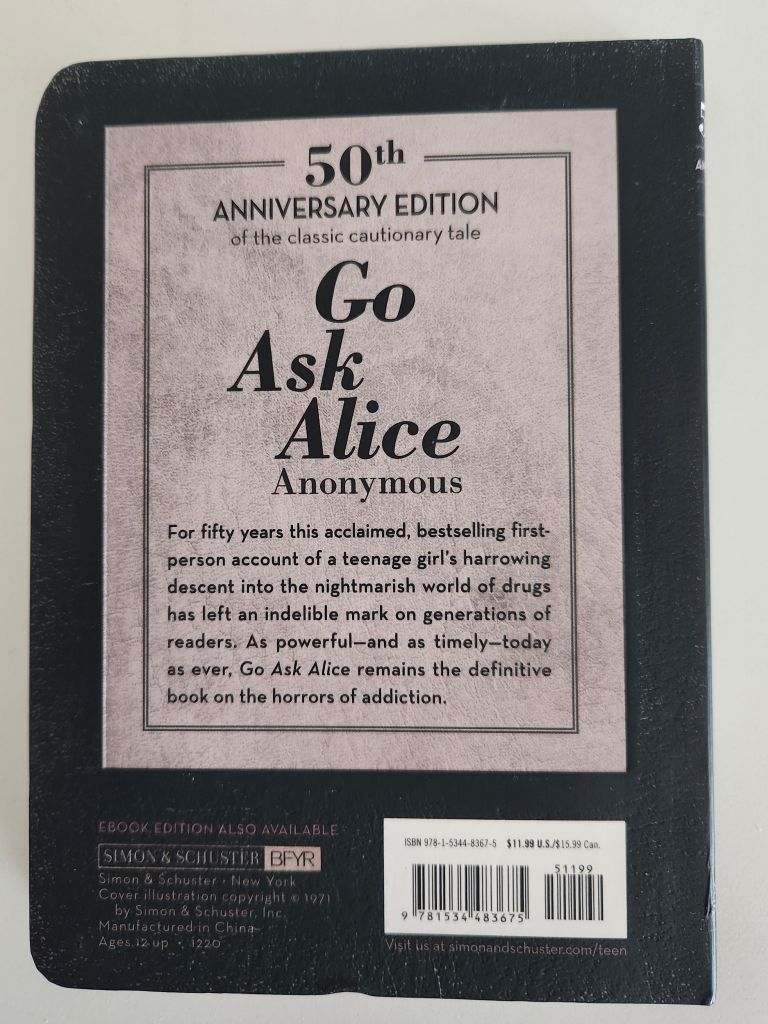

A couple of years ago, I purchased the 50th anniversary edition because I wanted to read it again.

I saw that Prentice Hall published its first edition in 1971. Then another publisher took it over. That it has never been out of print since then speaks to its continued popularity.

I noticed that there is a Forward written by “the editors,” which states “Go Ask Alice is based on the actual diary of a fifteen-year-old drug user…it is a highly personal and specific chronicle. As such, we hope it will provide insights.”

And yet, on the copyright page in tiny letters, it states, “This book is a work of fiction.” I suppose this covers them from a legal standpoint. But morally, shouldn’t they remove the forward? It’s misleading because it portrays itself as something “separate” from the story itself.

Also, I have not seen this first-hand, but I read that libraries still carry Go Ask Alice on non-fiction shelves. The book remains on many school reading lists.

If they offer full disclosure that it is fiction, that would be something else entirely. But it’s working for the publisher to keep it vague; to keep the details in the shadows, just like its disturbing cover.

I understand that the details of growing up in my home influenced my interpretation of everything I read. An author or publishing company can’t really foresee that. I don’t blame the book for that, but I felt like it drew me in because it was “true,” which created a lot of anxiety for me.

To this day, I still refuse to try a sleeping pill. And that’s the truth.

Leave a comment