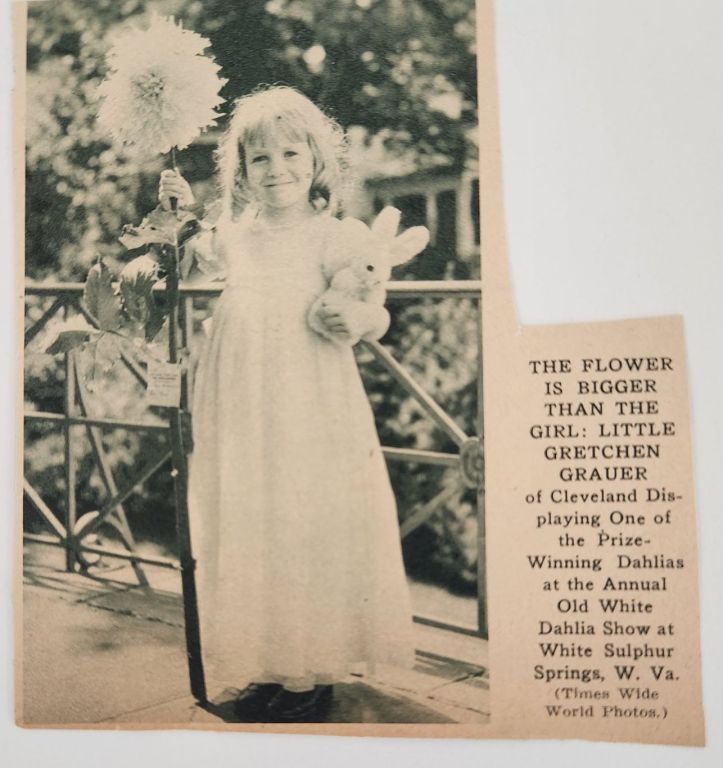

In August 1930, my mother’s life began with this birth announcement in a local Cleveland paper:

“Grauers Take Up Sculpture”

“Word comes from Maternity Hospital that Natalie E. and William C. Grauer have collaborated on a sculptural master piece, their first. It has been entitled Gretchen. It is modernistic to be sure; pleasantly stylized and its lines are robust and beautiful. It will be on exhibition from time to time, properly placed on a pedestal. It is not for sale.”

With that, mom’s life began as the daughter of two well-known, respected artists and teachers. Soon, Gretchen was riding her tricycle up and down aisles of students practicing their sketching and painting inside her parents’ Fine Arts Studio loft on Euclid Avenue in Cleveland. It sat above the “Korner Kupboard” restaurant at the back of the Fine Arts building. Sometimes, they could hear pianists for the restaurant warming up when they sat in the courtyard. She loved calling it her “bohemian” childhood.

She was her father’s only child and a beautiful little girl with soft blond curls. Natalie was a widow when she met Billie, and had brought her own daughter, Blanche, to the union when they married. There was an 18-year gap in the sisters’ ages. Basically, my mother was raised an only child, and her father, in particular, doted on her.

When she was a toddler, my grandfather was hired to paint a mural inside the Virginia Room at The Greenbrier Resort which blossomed into nine years of running an artists-in-residence program and art gallery during the summer months. Natalie was right by Bill’s side as co-director. She was a very modern woman.

For those nine summers, mom ran in the fields and watched polo games with a nanny and attended costume balls (Natalie made her dresses) with the other children of the Greenbrier guests. She particularly liked “Sunny” Crawford, who would later become the heiress and socialite who married Claus Von Bulow. This was the crowd she was literally running with.

Throughout my mother’s childhood, her height was probably measured standing next to various sizes of finished paintings her parents propped up against walls before being sold. Composition, luminosity, charcoal, shading, brushwork, matting, acrylics were all words my mother quickly absorbed. Her parents literally breathed art into her. Clearly, her world would always be about and influenced by art; for good and for bad.

She shared with me once that her mother told her she was “in the way of things” and got dropped off for weeks at a time (sometimes entire summers) with her aunts and cousins so Billie and Natalie could travel and paint landscapes in Maine, Canada and Mexico. There was always work or new opportunities to explore.

For Natalie, her passion for art pushed aside a lot of maternal opportunities. Or, maybe, this is who she was. What is that saying about “when someone shows you who they are, believe them?” I never met my grandmother, as she died before I was born. I never felt their relationship first-hand. I’m sure she enjoyed having a second daughter, and sincerely placed Gretchen on that pedestal, but she also left her there.

As a result, a disconnect was passed down from mother to daughter to her daughters. It’s almost an age-old tale of mothers and daughters. Issues slide right through in our DNA. So, what was mom’s burden became ours as my sister and I also struggled with a lifetime of emotional distance with her.

I grew to handle it as an adult, but as a child, I desperately wanted her attention. And one time, I thought I had found it through the perfect vehicle: art.

I had just turned 11 and opened my birthday card and found a new membership to the YWCA. I hugged both of my parents. The facility was just down the street from us, an easy couple of blocks to tackle with my bike. I started riding up to Lee Road immediately.

One day, after swimming, I was in the locker room changing out of my wet bathing suit. As I gathered the remaining items from the locker, I felt something on the top shelf. I was too short to see, so I stood on the wooden bench to figure out what was laying there.

There were eight sheets of construction paper. Most of them were different colors: red, orange, green and yellow. Each of them was heavy and loaded with beads, pieces of shells, glue and glitter.

I looked through all of them. They were busy and abstract. In my 11-year-old mind, I thought they were pretty good. I was already a veteran, of course, at recognizing good art.

I stood there holding them, an idea forming. Someone had obviously discarded them in the locker. I would take them home.

I carried them with me outside to the bike stand and rode home with my bathing suit rolled in a towel under my arm and the artwork in my left hand.

The next day I said “Mom, look what I did in school.”

“Oh, let me see” and she slowly looked at each one, nodding said “yes” or said “pretty” to most.

“I like these, sweetheart; can I keep them?” and I replied “yes” and walked away beaming; feeling only a small twinge of guilt.

Then the unthinkable happened. She called me back downstairs.

“I examined these and noticed something,” she said.

And that was when she turned them over, and there were first and last names, all different, written on every piece of paper. It never occurred to me to turn them over.

Of course, I got in trouble for that, and rightly so, but I wonder if she understood the impulse behind my actions. After all, it was art I had stolen. Art was supposed to be the gateway to her attention; her affection. I don’t know whether her heart ever did recognize her own attention-seeking memories in that encounter. We never spoke of it again.

Leave a comment